Using rpy2 in notebooks¶

rpy2 is designed to play well with notebooks. While the target notebook is jupyter, it is used in other notebook systems (some of them are based on Jupyter, or are managed Jupyter notebook systems).

rpy2 is working, and is sometimes available by default, with Google’s Colab, Databricks notebooks, AWS SageMaker, Azure Notebooks, or Google Cloud AI Platform Notebooks.

This section shows how rpy2 can be used to add everything R can offer to Python notebooks.

Note

This section is available as a jupyter notebook jupyter.ipynb (HTML render: jupyter.html)

from functools import partial

from rpy2.ipython import html

html.html_rdataframe=partial(html.html_rdataframe, table_class="docutils")

Data Import¶

We choose to use an external dataset to demonstrate how R’s own data import features can be used.

from rpy2.robjects.packages import importr

utils = importr('utils')

dataf = utils.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/jakevdp/PythonDataScienceHandbook/'

'master/notebooks/data/california_cities.csv')

The objects returned by R’s own read.csv() function (note that the R

function in the R package utils is called read.csv() while the

Python function is called read_csv() - rpy2 converts R symbols

with dots to underscores for Python).

rpy2 provides customization to display R objects such as data frames

in HTML in a notebook. That customization is enabled as follows:

import rpy2.ipython.html

rpy2.ipython.html.init_printing()

dataf

| X | city | latd | longd | ... | area_water_km2 | area_water_percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | Adelanto | 34.57611111111112 | -117.43277777777779 | ... | 0.046 | 0.03 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | AgouraHills | 34.15333333333333 | -118.76166666666667 | ... | 0.076 | 0.37 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | Alameda | 37.75611111111111 | -122.27444444444444 | ... | 31.983 | 53.79 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | Albany | 37.886944444444445 | -122.29777777777778 | ... | 9.524 | 67.28 |

| 4 | 5 | 4 | Alhambra | 34.081944444444446 | -118.135 | ... | 0.003 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 6 | 5 | AlisoViejo | 33.575 | -117.72555555555556 | ... | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 7 | 6 | Alturas | 41.48722222222222 | -120.5425 | ... | 0.036000000000000004 | 0.57 |

| 7 | 8 | 7 | AmadorCity | 38.419444444444444 | -120.82416666666666 | ... | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 480 | 481 | 480 | Yucaipa | 34.030277777777776 | -117.04861111111111 | ... | 0.013000000000000001 | 0.02 |

| 481 | 482 | 481 | YuccaValley | 34.13333333333333 | -116.41666666666667 | ... | 0.0 | 0.0 |

dataf.colnames

| X | city | latd | longd | elevation_m | elevation_ft | population_total | area_total_sq_mi | ... | area_water_km2 | area_water_percent |

stats = importr('stats')

base = importr('base')

fit = stats.lm('elevation_m ~ latd + longd', data=dataf)

fit

| 0 | coefficients | (Intercep... |

| 1 | residuals | ... |

| 2 | effects | ... |

| 3 | rank | [1] 3 |

| 4 | fitted.values | ... |

| 5 | assign | [1] 0 1 2 |

| 6 | qr | $qr ... |

| 7 | df.residual | [1] 431 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 11 | terms | elevation... |

| 12 | model | ... |

Graphics¶

R has arguably some the best static visualizations, often looking more polished than other visualization systems and this without the need to spend much effort on them.

Using ggplot2¶

Among R visulization pacakges, ggplot2 has emerged as something

Python users wished so much they had that various projects to try port

it to Python are regularly started.

However, the best way to have ggplot2 might be to use ggplot2

from Python.

import rpy2.robjects.lib.ggplot2 as gp

R lets is function parameters be unevaluated language objects, which is

fairly different from Python’s immediate evaluation. rpy2 has a

utility code to create such R language objects from Python strings. It

can then become very easy to mix Python and R, with R like a

domain-specific language used from Python.

from rpy2.robjects import rl

Calling ggplot2 looks pretty much like it would in R, which allows

one to use the all available documentation and examples available for

the R package. Remember that this is not a reimplementation of ggplot2

with inevitable differences and delay for having the latest changes: the

R package itself is generating the figures.

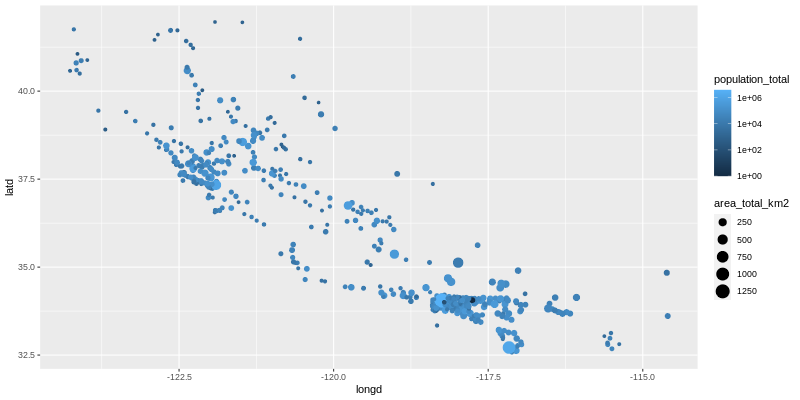

p = (gp.ggplot(dataf) +

gp.aes(x=rl('longd'),

y=rl('latd'),

color=rl('population_total'),

size=rl('area_total_km2')) +

gp.geom_point() +

gp.scale_color_continuous(trans='log10'))

Plotting the resulting R/ggplot2 object into the output cell of a notebook, is just function call away.

from rpy2.ipython.ggplot import image_png

image_png(p)

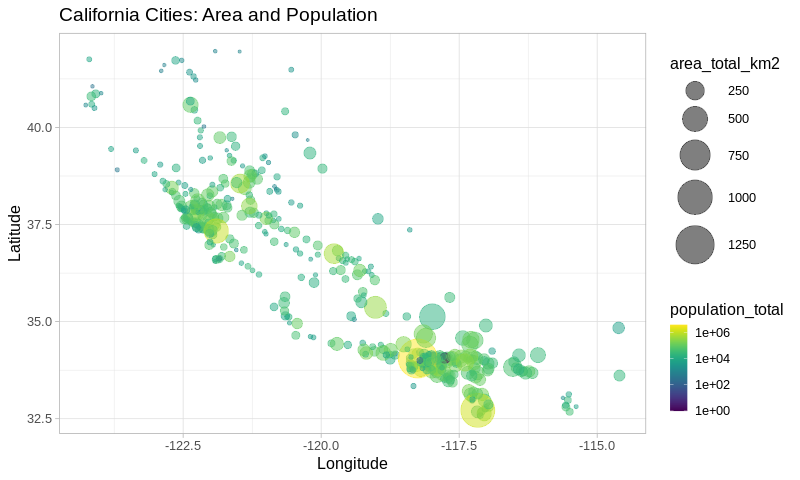

All features from ggplot2 should be present. A more complex example

to get the figure we want is:

from rpy2.robjects.vectors import IntVector

p = (gp.ggplot(dataf) +

gp.aes(x=rl('longd'),

y=rl('latd'),

color=rl('population_total'),

size=rl('area_total_km2')) +

gp.geom_point(alpha=0.5) +

# Axis definitions.

gp.scale_x_continuous('Longitude') +

gp.scale_y_continuous('Latitude') +

# Custom size range.

gp.scale_size(range=IntVector([1, 18])) +

# Transform for pop -> color mapping

gp.scale_color_continuous(trans='log10') +

# Title.

gp.ggtitle('California Cities: Area and Population') +

# Plot theme and text size.

gp.theme_light(base_size=16))

image_png(p)

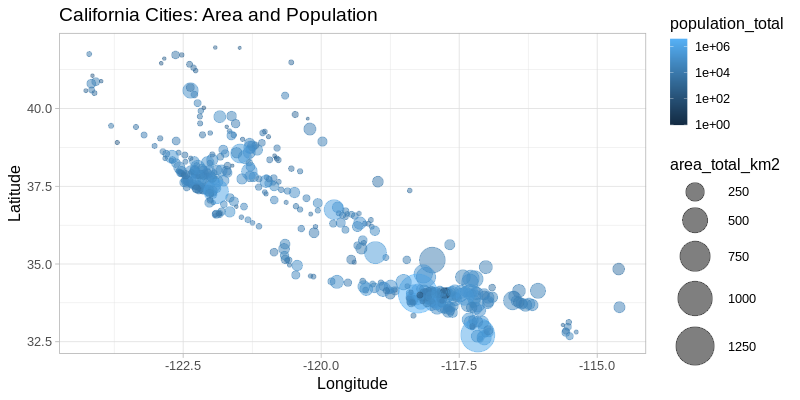

Using ggplot2 extensions¶

There existing additional R packages extending ggplot2, and while it

would be impossible for the rpy2 to provide wrapper for all of them the

wrapper for ggplot2 is based on class hierarchies that should make

the use of such extensions really easy.

For example, to use the viridis color scale, we just need to import the

corresponding R package, and write 3 lines of Python to extend

rpy2’s ggplot2 wrapper with a new color scale. A clas diagram with

the classes in the rpy2 wrapper for ggplot2 is available in the rpy2

documentation.

viridis = importr('viridis')

class ScaleColorViridis(gp.ScaleColour):

_constructor = viridis.scale_color_viridis

scale_color_viridis = ScaleColorViridis.new

That new color scale can then be used as any other scale already present

in ggplot2:

p = (gp.ggplot(dataf) +

gp.aes(x=rl('longd'),

y=rl('latd'),

color=rl('population_total'),

size=rl('area_total_km2')) +

gp.geom_point(alpha=0.5) +

gp.scale_x_continuous('Longitude') +

gp.scale_y_continuous('Latitude') +

gp.scale_size(range=IntVector([1, 18])) +

scale_color_viridis(trans='log10') +

gp.ggtitle('California Cities: Area and Population') +

gp.theme_light(base_size=16))

image_png(p)

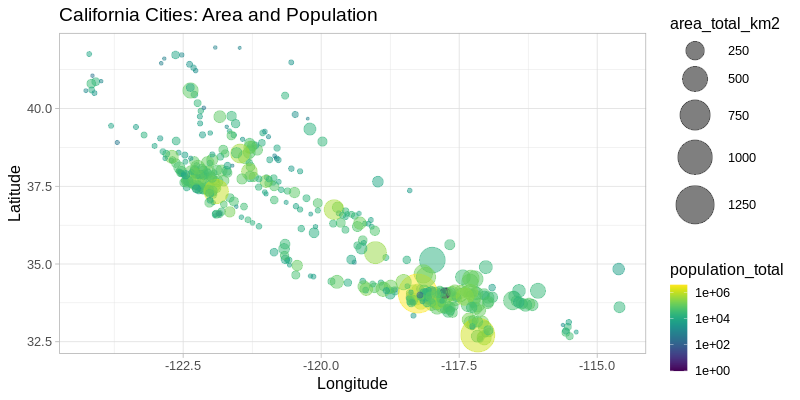

So far we have shown that using ggplot2 can be done from Python as

if it was just an other Python library for visualization, but R can also

be used in cells.

First the so-called “R magic” extension should be loaded.

%load_ext rpy2.ipython

From now on, code cells starting with %%R will see their content

evaluated as R code. If the R code is generating figures, they will be

displayed along with the rest of the output.

%%R

R.version.string

[1] "R version 4.0.5 (2021-03-31)"

%%R -i dataf

require(dplyr)

glimpse(dataf)

R[write to console]: Loading required package: dplyr

R[write to console]:

Attaching package: ‘dplyr’

R[write to console]: The following objects are masked from ‘package:stats’:

filter, lag

R[write to console]: The following objects are masked from ‘package:base’:

intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

Rows: 482

Columns: 14

$ X <int> 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 1…

$ city <chr> "Adelanto", "AgouraHills", "Alameda", "Albany", "Al…

$ latd <dbl> 34.57611, 34.15333, 37.75611, 37.88694, 34.08194, 3…

$ longd <dbl> -117.4328, -118.7617, -122.2744, -122.2978, -118.13…

$ elevation_m <dbl> 875, 281, NA, NA, 150, 127, 1332, 280, 14, 48, 132,…

$ elevation_ft <dbl> 2871, 922, 33, 43, 492, 417, 4370, 919, 46, 157, 43…

$ population_total <int> 31765, 20330, 75467, 18969, 83089, 47823, 2827, 185…

$ area_total_sq_mi <dbl> 56.027, 7.822, 22.960, 5.465, 7.632, 7.472, 2.449, …

$ area_land_sq_mi <dbl> 56.009, 7.793, 10.611, 1.788, 7.631, 7.472, 2.435, …

$ area_water_sq_mi <dbl> 0.018, 0.029, 12.349, 3.677, 0.001, 0.000, 0.014, 0…

$ area_total_km2 <dbl> 145.107, 20.260, 59.465, 14.155, 19.766, 19.352, 6.…

$ area_land_km2 <dbl> 145.062, 20.184, 27.482, 4.632, 19.763, 19.352, 6.3…

$ area_water_km2 <dbl> 0.046, 0.076, 31.983, 9.524, 0.003, 0.000, 0.036, 0…

$ area_water_percent <dbl> 0.03, 0.37, 53.79, 67.28, 0.01, 0.00, 0.57, 0.00, 0…

The data frame called dataf in our Python notebook was already bound

to the name dataf in the R main namespace (GlobalEnv in the R

lingo) in our previous cell. We can just use it in subsequent cells.

%%R -w 800 --type=cairo

cat("Running an R code cell.\n")

p <- ggplot(dataf) +

aes(x=longd,

y=latd,

color=population_total,

size=area_total_km2) +

geom_point(alpha=0.5) +

scale_x_continuous('Longitude') +

scale_y_continuous('Latitude') +

scale_size(range=c(1, 18)) +

scale_color_viridis(trans='log10') +

ggtitle('California Cities: Area and Population') +

theme_light(base_size=16)

print(p)

Running an R code cell.